January 19, 1861

The colored woman had been many things. A suckling babe and a nursing mother, a fancy servant and a field hand, a lover and a concubine, a slave and a freewoman.

And now she was old.

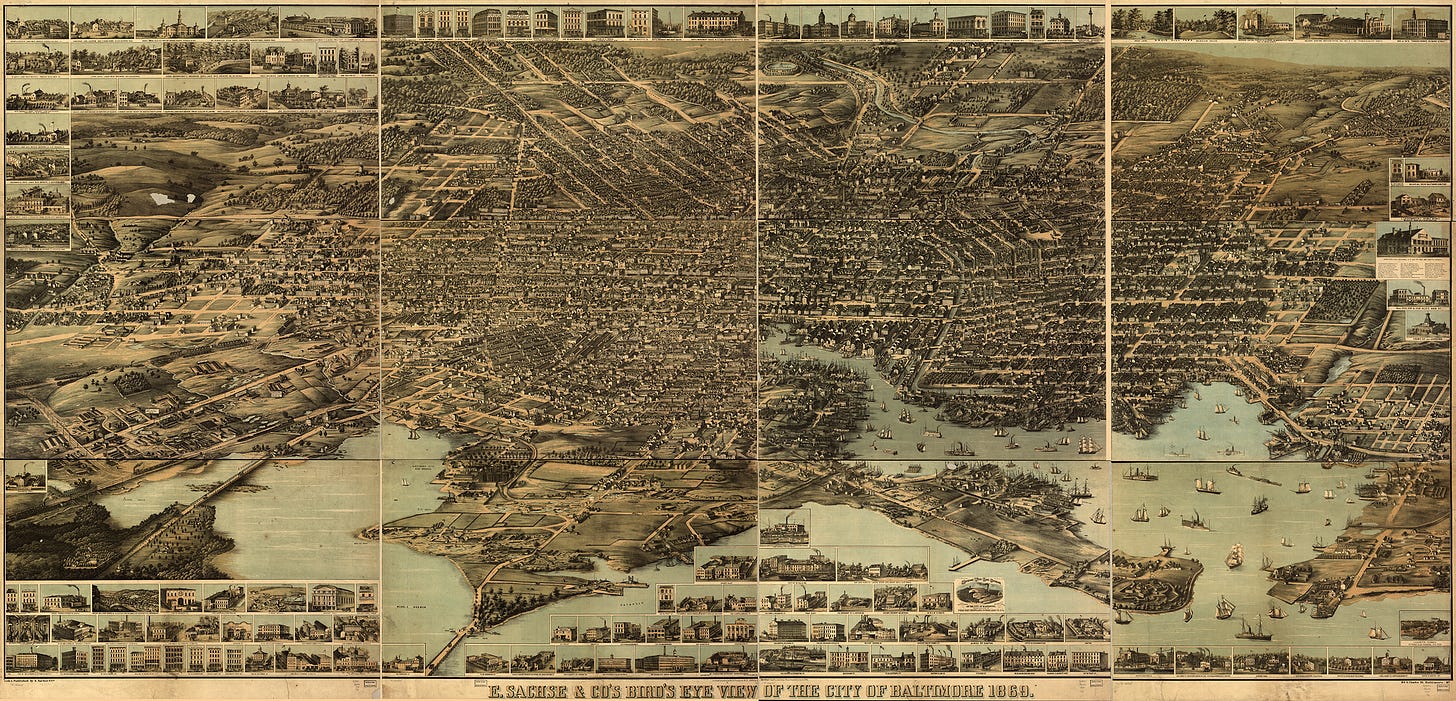

Shaking her head, she tugged the calico quilt across her shoulders while trudging alongside the Baltimore wharves. She passed the ramshackle Fountain Inn, where George Washington and Thomas Jefferson once stayed while church bells tolled for the joyous freedom and liberty they done brought to America.

Today, the decaying hulk of the ancient building seemed to waver in the cold wind whistling through the ship masts.

“Them chills,” she moaned, glaring at the murky waters.

She strengthened herself.

“Go down, Moses. ‘Way down to Egypt's land,” she sang. “The Good Lord sent Moses to Pharaoh. And Moses done say, oh! let my people go!”

The cobblestones underneath her feet were uneven and she stumbled.

She looked around quickly and didn’t see anyone she recognized. Least not brandishing the whips of her nightmares.

“Pharaoh, Pharaoh! I'll smite your first-born dead! Oh! let my people go!” she angrily sang.

For she’d a journey to make.

For didn’t the Good Lord tell her what to do?

“It ain’t be no good,” she muttered, thinking of the man she must seek. “He ain’t help! And I be one to arsk him! Me a dad blasted lick spittle! Hell and tarnation!”

She slapped her sides and broke into a hum, pushing through the crowds of idle stevedores towards her destination. She ignored the staring faces in passing warehouses buttressed by huddled rows of shacks selling cheap fruit, coffee and candy, the dirtiest pickings from the filthiest ships from the Indies and further abroad.

“Ain’t gonna touch that,” she said, recoiling at the shriveled fruit and grubby candy piled high, attracting just about every damn bug in the damned state of Maryland.

More appetizing was whiffs of fried oysters, made tantalizing by the colored men crying, Oysters! Oysters! Get chore oysters heah!

Her stomach rumbled. “Ain’t got a penny,” she mourned.

A sailor leered.

She grinned.

He turned away at the sight of her teeth and she laughed.

Then she grew serious. She hadn’t much choice. Colored women never did, free or enslaved. “This be the Good Lord’s test I be awaitin’ all my life? Afore I can reach the Promised Land?” she wondered.

She turned away from the harbor onto Calvert Street only to be startled by a stern Indian. “Hell and tarnation!” she shouted.

She reached out to slap the wood face outside a tobacco shop, but then stopped and laughed.

“Fool I am,” she said, her voice rising to a sing-song. “You ain’t him! You ain’t Pharaoh. But cain’t stop. Cain’t forget what the Lord tole me to do, even if I be a dad blasted lick spittle!”

Courage rose in her.

“Oh! Go down, Moses, away down to Egypt's land. And tell King Pharaoh! Tell King Pharaoh! To let my people go!”

Now she passed narrow alleys with boisterous noises and the stink of stale beer from dank taverns, intermingling with tar, sea water, musty ships, spices and guano, those rich odors of harbor life delighting men and driving away ladies who claimed to be respectable.

Pharaoh could be in those taverns…

Her heart lurched.

In her mind she saw a man with a mane of hair glinting like a golden crown in a fierce sun.

He turned and stared at her, and she felt the heat and dust of Egypt pour onto her face and the sting of whips across her back.

She blinked.

“Silly lick spittle,” she admonished herself as the cold wind picked up. Her heart still pounded as she scampered ahead.

Baltimoreans liked to boast that their city sat on seven hills, a modern day Rome, and adding a provincial grandeur to the domes and monuments of the self-proclaimed Monumental City. And now Calvert Street rose upwards, seemingly as insurmountable as the mountains of the wilderness the Hebrews wandered through for forty long years.

The old woman thumped her chest. She coughed. “I’d be lucky if my legs ain’t fall off afore I get there,” she complained.

When a passing shopper frowned, she laughed and laughed once more when the lady tugged her parcels closer and hurried away.

She knew the look. She saw it every day. The silent eyes saying: ‘we don’t see you even if you be inches from us. We pretend you ain’t there. ‘Cause we don’t like colored folk.’ Most white folk were like that, even them who tutted at slavery and wrote letters in support of them abolitionists up in Boston so they ain’t feel guilty no more.

“Ain’t no one like an ol’ colored woman. Ain’t no one gonna bother an ol’ colored woman,” she wisely observed. “‘Cept him. Cain’t ever trust him. Not Pharaoh.”

She reached Baltimore Street. Shoppers filled the city’s main thoroughfare, even if there were fewer in these uncertain days.

Fancy new brownstones loomed above the squat brick stores of earlier generations. Dotted here and there stood even newer cast-iron facades with plate glass windows crowded with English woolens, French china, New York furniture and an endless array of factory-made goods, proclaiming innovative progress and a bold future for white folk across America.

‘Til November 6, 1860, put a screeching halt to everything.

The colored woman stopped halfway across the street, ignoring the clattering hooves when wagons and buggies frantically veered across the horsecar tracks to avoid her.

“Ain’t gonna go through Monument Square!” she warned herself.

She knew if Pharaoh ain’t in the taverns, he be in the fancy saloons in the hotels ‘round the square, with his boys who liked nothing more than likker and hating colored folk.

“Hell and tarnation!” she said, her red turban shaking.

The detour meant when she arrived at the base of Saratoga Street, she faced the steepest climb to her destination.

Feral boys ran past her, hooting and rattling sticks against iron railings. An urchin leapt to the top of a stoop.

“Georgia! Georgia! George----iiiiiaaaa gonna go!” he shouted, banging on the door.

An upper window flew open. A bespectacled face poked out. “Do tell! What news have you there?”

“Georgia gonna go!”

“By the horn spoon! Didn’t know Georgia already voted! I’ll be damned! Where’d you hear it? The papers?”

“The teleygraphs! Somethin’ big gonna happen! Down at Monument Square! You’d better pull foot to hear it. The Eyetalian gonna tell all!” the urchin hollered back.

“That damned dago?”

The urchin laughed. “Georgia! Miss’ippi! Aleebama! Floriee-dah! South Carylina! Yee-haw!”

The first-born sons of Egypt were already gathering, the colored woman wisely observed. Hath not the Good Lord already forecast it?

The bewhiskered face broke into a grin and he flipped a coin through the window. The urchin leapt off the steps after it and crashed into her.

Trash! she wanted to shout. Ignorant no-good white trash! Son of a two-bit cracker whore!

“Pretty chile,” she instead said, wheezing and gnashing her jaws into forcing a smile.

The urchin untangled himself from her quilt. “Get orf, you old nigger,” he shouted, running away.

She muttered but the quilt had protected her, and she had work to do.

She thought of her mistress with unexpected venom. “A right ol’ strumpet she is. Ain’t the only woman in Baltimore pertendin’ to be a lady with fine airs and fancy clothes. Hah! Her who loves him and afraid o’ him at the same time. He be the most dangerous man in all o’ America! Him who be Pharaoh! Ain’t be a more evil man who done walk on this earth!”

The colored woman climbed the hill and turned onto Courtland Street.

She remembered the rowhouses bein’ built not long after the war with the English in eighteen-oh-twelve. People gasped and said it be too far from the harbor. Then this cussed town kept growing and the marble-topped parlor tables and mahogany sideboards migrated even further northwards, leaving Courtland Street for the lawyers who couldn’t afford the new buildings by the courthouses.

She unfolded a precious paper, its letters a mystery.

Once more she heard the name, Jude Royer, said to her in a gravelly voice.

She matched the numbers to the ones painted above the door. Three floors towered above her. Boards by the door listed the names of the offices, but she already knew which one to go to. Second floor, front room.

She stared at the dark windows.

Had she come to the right man?

“He ain’t gonna help,” she decided. Only a fool would believe the tale she’d tell, ‘cause she couldn’t tell him everything. For she was a dad blasted lick spittle!

She daren’t mention Moses, for he’d laugh and disbelieve her.

And as for Pharaoh….

Pale faces of past masters and mistresses marched through her memories. Her legs sagged and she gripped the railings. She knew too well what evils hid in the heart and mind of law-abiding folk. She’d spat in the face of the devil hisself and nearly died for it. And she’d walked through the desert wilderness of her life for many more than forty years.

There’d even been times when she’d tried to will herself to die, wondering why would the good Lord let her live?

Now she knew. The Lord wanted her to find this terrible secret and what she must do about it.

For Moses had come. And through him she’d finally glimpsed the Promised Land.

A chance for justice.

Not the false pride in the freedoms and liberties white folk proclaimed from the Declaration of Independence they ain’t give to everyone. Not the sham piety rich folk bought for themselves with their fancy churches where they sat, preenin’ in their Sunday-best silks as if the Lord done care what they wore.

But true justice, for all men and women, white and colored.

She strengthened, belief and resolve growing in her.

“Oh! Go down, Moses,

Away down to Egypt's land,

And tell King Pharaoh

To let my people go….”

The colored woman turned the door handle and the gloom of the hallway enveloped her.

She had a sudden insight into the future, and it was not good.

But maybe, she hoped, afterwards she’d be free, truly free and not ‘cause a bit o’ paper she couldn’t read said so.

****

To return to Table of Contents: Link