Chapter 10

Eye for an Eye, the Trojan War and the birth of Modern Justice

Sunday, January 20, 1861

Jude Royer hurried up the alley away from the cells into fresh air.

Insofar what could be called fresh.

Ernst’s sudden grip saved him from the droppings from a paddy wagon crammed with the Saturday night drunkards. Half a mile to the southwest stood the train station for Frederick and Jude wanted nothing more than to run away from Baltimore and Matthew Swann, justice be damned, till he remembered what awaited him at home.

But he was even more worried about the shock of the anger he’d felt in the cells. He knew this…dark fury…existed deep inside himself, but he’d forgotten how strong it could be.

He inhaled deeply, afraid of himself and his feelings.

“What do you think of Mr. Swann’s imprisonment?” Ernst asked.

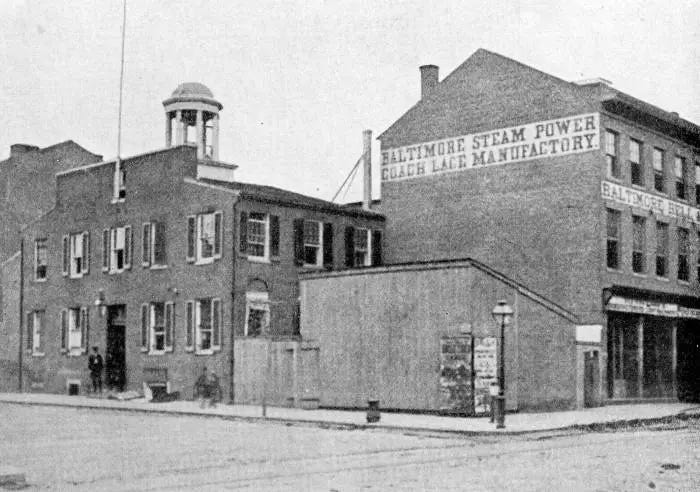

Jude glanced at American flag above the squat station house. He shook his head and not until they were out of sight and around the corner of Holliday Street did he come to a stop in front of the shuttered windows of the Baltimore Bell & Brass Works.

“Matthew should be fine as long as the damned letter from the Palmettos is never found,” Jude said. “At least I hope so. The Congressional investigators will make him uncomfortable but without the letter they have nothing except circumstantial evidence.”

He sighed. “Matthew always waits for people to rescue him. He asks for help and does nothing to help me. Why shouldn’t I walk away from his problems?”

“Mr. Swann should be the least of your problems,” Ernst agreed. “So why do you feel so strongly about his arrest?”

“Who says I do?” Jude retorted.

“You broke the table,” Ernst reminded him. “I almost thought you were going to punch him. You are much stronger than you think. It even surprised me. I can see that under your long coat and scrawny clothes is a body that must be nothing but muscle.”

Silence should speak what Jude wanted to say about Ernst’s unintentional insult, but he knew Ernst wouldn’t take it for an answer. He instead thought of the dark fury, a damning force of anger and frustration seeming to have a life of its own, threatening to take over his body and make him do things he didn’t want to.

He did not know what to make of it. And there was something else about the fury he still struggled to acknowledge.

He stared across the street at the gas works, thinking that the unpredictable gas, prone to explosion if you didn’t handle it carefully, matched his own private fury.

“I felt something in my fingers and in my blood. I felt my hair rise,” Jude finally admitted. He pulled off his old hat and ran his fingers through his hair. They were still warm. “I felt scared. I felt anger.”

“You were scared because you saw injustice before your eyes,” Ernst theorized. He tapped Jude’s forehead. “This is the fear in your brain telling you to protect yourself at all costs, especially when the situation is not of your making. Run away! Not my fault! Not my problem!”

Ernst’s finger moved to the middle of Jude’s chest and suddenly jabbed him hard. “But in here, Jude Royer’s heart is beating. Hard. With flashes of heat and anger. Mr. Swann has knocked your world out of equilibrium. When you face pain or dangers, what happens? The primeval instincts takes over. You wince. Your body flinches. Your eyes hide away. Then the hands bunches to deliver the blow against the dangers. You want revenge against those who dared threaten you! Vengeance! Justice! You experience all these feelings of self-preservation, these instinct to fight back when threatened, just as the child or the savage today still lashes out when they feel assaulted.”

The German looked over Jude. “Oh, I see the protest in your face. You are civilized! But I know you must still feel the primitive justice buried within these emotions! The original justice! As a boy you must have pushed away a mother bearing a spoon of bitter tonic or a doctor prodding you with a sharp instrument as he attempted to inoculate you against smallpox? Or imagine vengeance against parents for punishing you unfairly?”

Jude certainly did remember. “These are childlike behaviors,” he still argued. “Of children who know little of the world. They can be forgiven. You cannot compare them to adults.”

“Except the child never forgets,” Ernst pointed out. “Children are fascinated by death and punishment. They understand in that innate way of theirs, much more than we adults would like to admit. It allows them to so casually play games of Indians and the cavalry, shooting and tomahawking each other. Children recognize this brutal form of justice based on revenge and which is why they are capable of astonishing cruelty. And when the child becomes an adult, he still strikes out at his son for violating the order of the house. The mocking and taunting languages of adults reflects our desire to lash out when frustrated and angry.”

Jude looked studiously at the worn brim of the top hat.

“It is to the savages we now must look to understand vengeance,” Ernst said, “to understand this original craving for justice we are all born with, without the veneers of education and dubious morality trapping civilized man into thinking he is better than the barbarians of old.”

He nodded thoughtfully, watching Jude. “I once read a most fascinating book called History of the American Indians by a Scotsman named James Adair, who dwelt among the Cherokee tribes in the last century. Adair observed that when murder happens, the Indian’s heart burns violently day and night until he has shed blood for blood. They carry from father to son the memory of the murder, which never dies until it is avenged.”

Jude stared ahead.

Ernst squinted, thinking of memories. “And it’s found among the peasants of the primitive parts of Europe. Alberto Fortis, an Italian traveling in Dalmatia, wrote of how peasant women showed their sons the bloody shirts of slain fathers to incite them to revenge. The savages and primitive men never forgive. Without vengeance, there is no justice; without justice, they are incomplete, no longer human and living in a helter-skelter world out of balance.”

Ernst placed both hands squarely on Jude. “Sneer at the savage if you wish! Then remember what I said last night. How justice is the passion for vengeance or the sentiment of equality! Both promise the equilibrium all men seek as a fulfillment of life.”

Then Ernst suddenly jabbed Jude’s chest again. “But never forget, Jude Royer, no matter what you tell yourself, how we feel the need for a just equilibrium in the heart. The instinct that through vengeance you will restore equilibrium in your life is a powerful one. Eye for an eye! Who does not understand this simple concept! And vengeance is the oldest of human passions, right alongside lust! Possibly older than even love. I am sure your actions shocked and scared you, but if you did not feel sympathy for revenge, you would not be human, Jude Royer.”

Jude glanced at Ernst.

“The Protestant self-denial!” Ernst said, laughing even if mistakenly. “It’s admirable but it is not always healthy.”

Jude coughed politely.

“Which is why I also know you are a good man,” Ernst persisted. “You apologized to Matthew. And yes, it made a difference.”

“I am a civilized man,” Jude finally said, putting his hat back on. “I crave, like most do, the peace of a stable equilibrium. But if I felt the call for vengeance, then why is it wrong? Why shouldn’t I attack Matthew? You described revenge as the original justice. Why is it not the true justice?”

“True justice? But how could you harm Mr. Swann? Who is already in trouble. It is why you are also so angry, for you suspect two wrongs do not make a right. Perhaps you recognized vengeance can be more trouble than it’s worth? Perhaps it invites other problems? Perhaps, just maybe, it is the source of evil in our own actions.”

“Evil…” Jude murmured.

Ernst nodded. “Which is why despite our sympathies for the vengeance of the primitive men and the simple child, we also know it cannot be true justice. A good man recognizes those instincts of ours and understands while they can be listened to, it is not always to be trusted. It is how we act upon those instincts which makes the difference, and the choices we make is far more important in defining real justice than these primitive instincts.”

He smiled encouragingly. “I would not fear these thoughts, Jude, for they mean you are now asking the proper questions about justice.”

Jude thought of the dark fury inside him. There was still the problem with it he was struggling to admit. “Then what is justice?” he demanded.

“We cannot come to an answer before you learn more.”

Jude scoffed. The tidy blocks of brick storefronts lined with wood awnings and the tall church steeples of Baltimore were as civilized as any place as he’d ever seen. The gas lamps on the street corners and the distant locomotive whistle symbolized a world that had rapidly changed in his short lifetime.

Americans took great pride in the building of their civilization, believing the sacred freedom and liberty enshrined in the Constitution was leading them to a world more just and true than past generations. The great prosperity engendered by American progress was surely a just reward .

As if reading his thoughts, Ernst added, “Civilized society too often ignores how justice can be deeper and more personal. Because of our fears of the barbaric vengeance, we cloak justice safely in words, within books or inscribed above courthouses, and in a way, miss its origins and why it’s so innately important. We must go back to the earliest days of civilization to see why justice first moved away from vengeance, which will also help us understand the evolving meaning of justice throughout history to this day. Remember the package I gave you! These plays will explain much, including these feelings you experienced.”

Jude had forgotten the books. He removed the package from his valise and untied the twine. The paper slipped away to reveal three slender volumes.

“‘Medwin’s translation of Aeschylus’s Oresteia,’” Jude read aloud, puzzled. The he snorted. “Plays? Ernst! Aren’t these Greek mythologies? Made up stories by pagans to explain a world they didn’t understand? What do plays have to do with justice?”

****

To return to Table of Contents: Link

James Adair spent 40 years living and trading wholly among the American Indians deep in the wilderness of the American southeast, particularly the Chickasaw and Cherokee tribes. His book was originally published in 1775 and be found on Gutenberg.

A region almost as culturally isolated as the pre-Revolutionary American southeast was Dalmatia. Alberto Fortis, a Venetian traveller, published Travels into Dalmatia in 1778, his studies of the rituals, culture and tradition of an indigenous people he called Morlachs.