Chapter 4

Riot!

Saturday, January 19, 1861

More firecrackers seemed to be going off in the direction of Monument Square. Or thunder. Or a fast-moving buggy on the cobblestones. None of it mattered to Jude Royer when staring at his mother’s handwriting on the envelope given to him by Ernst.

He knew Matthew would count to five minutes to ensure the German was safely gone before returning to the office, but for once he appreciated the time the foolish secessionist had inadvertently bought him.

Jude studied the envelope. His mother’s script was too careful, the slow scrawl of someone who’d learned spelling by tracing copperplates as a child and who’d written barely a dozen times since.

Then anger began to rumble in his stomach.

Jude Royer did not see the world in black and white, despite what Ernst claimed. He admired the German’s intelligence and accepted his friendship, but Ernst little knew how superior he sounded or unwanted his inquisitive observations were.

Only one person knew the true Jude Royer. No one, least of all Ernst, knew what he really thought inside the carefully guarded privacy of his mind. And right now dark thoughts were surfacing, thoughts he’d never tell anyone. He quickly stashed the letter away in his frock coat, unread, and then remembered the scrap left by the colored woman and unfolded it.

Little more than a sheaf torn from a pamphlet, someone had scrawled his name and address on one side. The other side revealed a partial name in printed type: force Joh….

Something-force John? Johannes?

The grubby paper was much folded as if someone had spent many an hour fingering it. Did this mysterious force Joh give the colored woman the name and address of Jude Royer?

Jude had been careful in establishing his name in Baltimore, knowing the truth of his origins could lose him clients. Who, among the Baltimoreans he knew, would send a colored woman to him?

A thought flittered through his mind,

But he dismissed it. Shrugging aside the irritating mystery, he instead carefully folded the recently completed brief and tucked it safely inside the tall stovepipe hat and squared it on his head with a smack of satisfaction and then brushed imaginary dust off his black coat.

He liked the studious propriety implied by the color of his clothes, for black dye was expensive if you didn’t want something that faded in weeks, and he eschewed the dubious plaid and brightly colored waistcoats and trousers worn by other men as hallmarks of vaguely untrustworthy minds.

Matthew sidled back into the room. “Damn German,” he muttered.

“You aren’t going anywhere this afternoon?” Jude asked, suddenly remembering what he’d promised to do.

“Must go to the courthouse too, so I shall go with you.”

His heart sank. “Why?”

“Oh,” Matthew said with vagueness. “A will needs to be filed.”

“Hmph.” Jude pursed his lips. “I’ve been informed that it’s safer to stay indoors today. There may be an assembly in Monument Square. It could turn violent,” he speculated.

“You’re still venturing there,” Matthew pointed out. “Georgia’s supposed to secede today. And, oh, my dear Jude! Haven’t you also heard? I have it on the greatest authority that Unionist forces in Baltimore are planning cut the telegraph lines! All to hinder news from reaching our brethren across the South! If there’s an assembly, I must be there to show my support!”

Fools, Jude thought. He wrapped his muffler around his neck. The world seemed to be filled with fools, more fools and damned fools, and he resented being drawn into their paranoia.

He gave Matthew an abbreviated account of his visitor.

But Matthew surprised Jude when a wide grin broke across his chubby face. “I know what it must be.”

At Jude’s askance expression, he added, “I assure you there’s no danger! It’s peculiar they sent a Negress to you. It must be part of their challenge. You see, they’re testing me.”

It was not the reaction Jude expected and a slight disappointment did mingle with his relief. “A test? By who?”

“Forget your visitor,” Matthew said magnanimously. “We shall find nothing but friends in Monument Square and I shall take you out for a celebratory toddy in Barnum’s afterwards! Come, let’s go now!”

The prospect of a hot drink in the fanciest saloon in town didn’t appeal to Jude. The colored woman had been insistent, and he gave Matthew a fleeting look of incomprehension, from the paisley cravat down to the highly pointed calfskin shoes in a brown shade too close to purple for comfort.

But eager to have the affair wiped from his hands, he didn’t protest. He wasn’t Matthew’s guardian angel or a hero rescuing people. And, still glancing at the shoes, Jude thought of his own black boots which he rigorously cleaned with blacking every week. Sensible and durable, such footwear told the world Jude Royer wasn’t given to extravagance and especially not flights of fancy. Which was exactly what he wanted the world to know.

The two lawyers stepped down the front stoop, near identical in their long coats and scarves and stovepipe hats. They hurried along Courtland Street and down the steep hill to Calvert Street just below the train station only to find their path blocked by a large crowd.

“Wonderful!” Matthew cried, panting in the frosty air. “Look how loyal Baltimoreans are!”

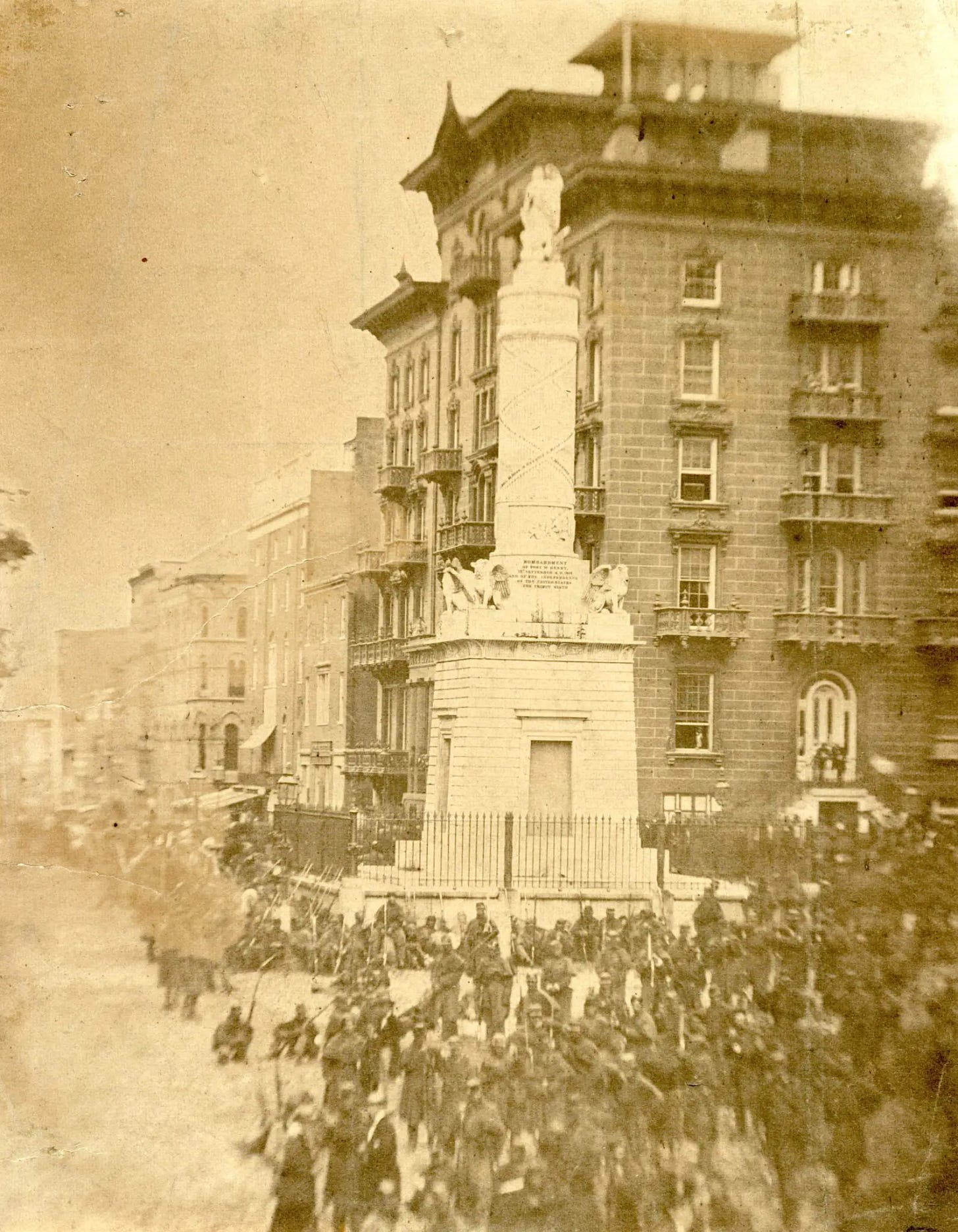

Hundreds of men filled Calvert street, spilling into nearby Monument Square. Jude tried to see any commotion, but the mass of bodies blocked his view.

Did the old woman really know something?

Jude felt a shiver up his spine that he tried to ignore as ridiculous. But even if Matthew should only slip on the cobblestones, he’d be damned if he’d have it on his conscience. “Matthew, maybe you should go home,” he urged.

Matthew pooh-poohed his concerns and looked eagerly around the little square.

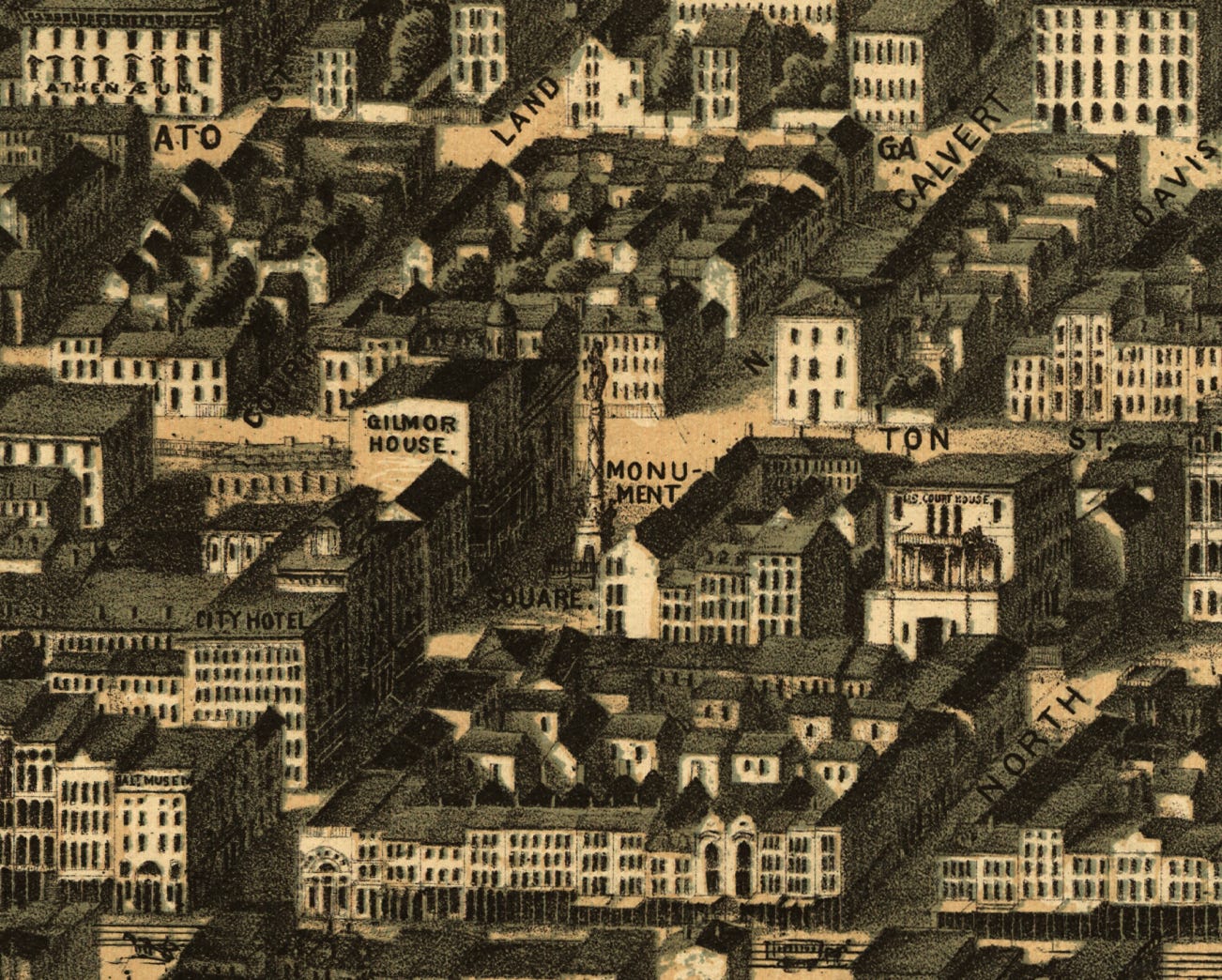

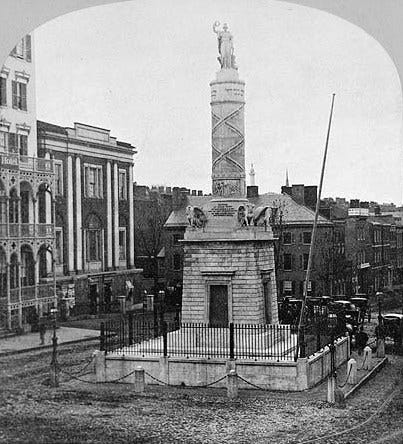

Monument Square had once housed Baltimore’s first courthouse, a peculiar structure older residents still remembered for sitting on stone arches to allow wagons to pass underneath it as the city grew northwards. Then the city eventually built a new courthouse to one side and turned the square into a plaza housing the Battle Monument, a homage to the War of 1812.

Although Exchange Place several blocks away was larger, Monument Square remained the most popular gathering spot in the city due to the hotels fronting the square, the stores and convention halls on Baltimore Street a block south, and to the east, proximity to City Hall, the Odd Fellows’ meeting lodge, the somewhat disreputable Holliday Street Theatre now owned by Ford’s of Washington, and the whorehouses.

Jude took in a panoramic sweep of the square and diagonal across from him rose the seven-story brownstone bulk of Barnum’s, Baltimore grandest hotel and famous for its dining tables groaning under lavish servings of terrapin soups, deviled crabs, oysters, roast canvas backs, old ham, rare wines and fine madeira, attracting gourmands from all up and down the East.

Further up the square stood the yellow façade of the St. Clair Hotel with its ornate cast-iron porch. North of the St. Clair sat the city’s replacement halls of justice, a squat brick courthouse with the fanlight windows of half a century earlier and fronted by a vaulted stone terrace perched above the square, but already dowdy next to the modern grandeur of the hotels. Large rowhouses, long since converted to offices, lined the opposite side of the square.

Only the old-fashioned Reverdy Johnson house remained a private residence and was still occupied by the jurist and defense lawyer made famous for defending the owner of Dred Scott in the landmark 1857 Supreme Court case that declared a slave was always a slave anywhere in America, even in the free states. The ruling meant that the security of escaped fugitive slaves in the northern states evaporated overnight, leaving abolitionists across America howling in bitter anger.

In looking at the large house and reflecting on the peculiarities of their times, Jude also wryly noted that Johnson was known for his anti-slavery attitudes and staunch unionism. Even so, his house was locally more famous for being looted during the Baltimore bank riots of 1835, following the failure of the Bank of Maryland that saw thousands of depositors lose their savings.

Angry mobs had stormed and looted the homes of the bank’s directors and burned the fine furniture from the Johnson mansion in massive bonfire in the square. The state later paid a fortune in compensation to Johnson and the other directors, while the depositors got nil.

But it was the same Baltimore mobs, also famous for anti-immigration and anti-negro violence, who’d earned the city the unpopular nickname of ‘Mobtown’ and the square had seen many riots in its day.

Upon completing his legal training in Philadelphia and announcing his intentions to settle in Baltimore, Jude’s Philadelphia friends tried to warn him that Baltimore was the most violent city on the East Coast, but he’d shrugged off their concerns, pointing to recent political reforms that seemed to have calmed the violence.

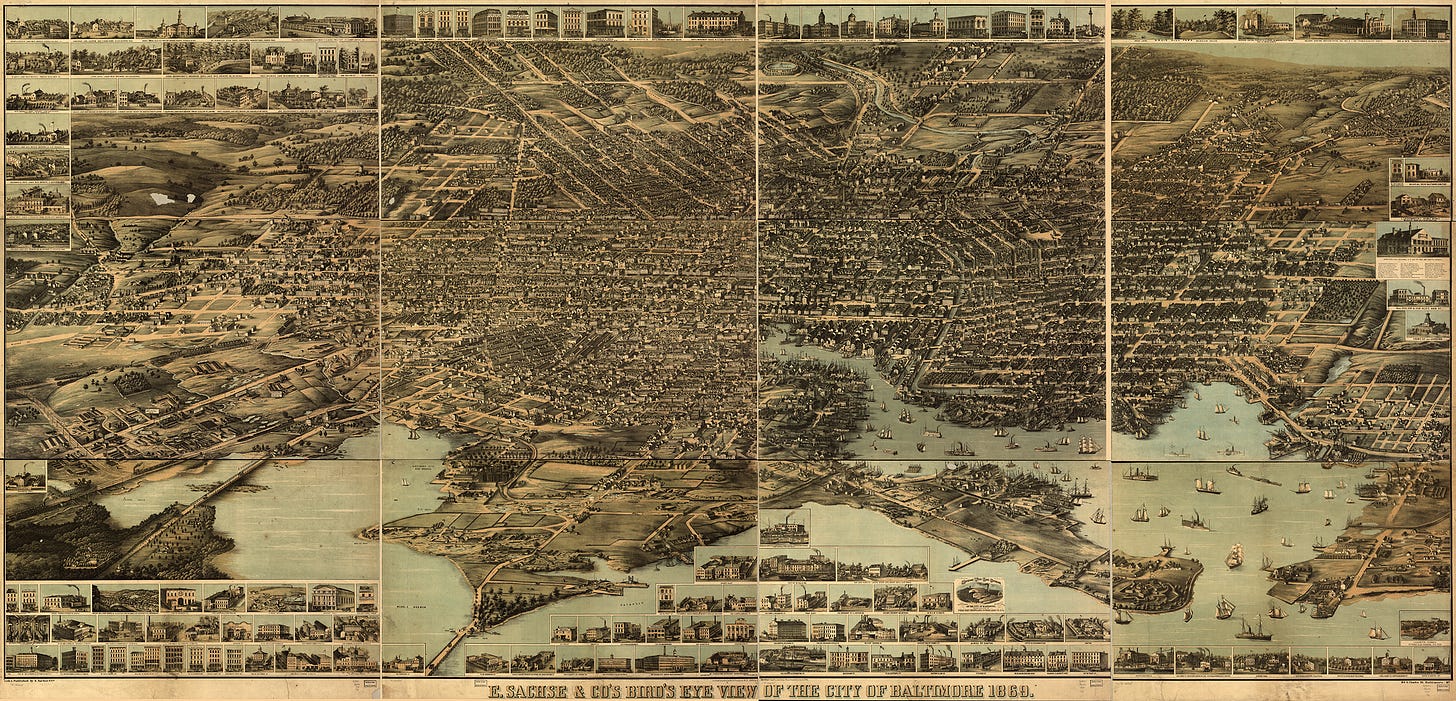

Jude had liked Baltimore from his first visit, with hills rising from the harbor in contrast to the flat gridded monotony of Philadelphia. From the little harbor nestled in the inner basin of the Patapsco River, he’d marveled at how the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad snaked westwards deep into the hinterlands of America, to Cincinnati and St. Louis, sending out more than 30 trains daily loaded with imported English cloth and factory-made goods, and returned with corn and wheat from the American hinterlands, destined for Europe and the Indies, along with coal and timber from the Appalachian mountains that fed the extensive iron foundries now employing a quarter of the city’s labor work force.

In the last few years Jude watched as rapidly multiplying coal yards, lumberyards, foundries, steam engine manufactories, glassmaking plants, paint factories, packing and canning houses and lumber mills jostling for space alongside the waterfront, competing with the shipyards and chandlers and warehouses. To this same harbor, under his very eyes, boats from Maryland tobacco farms and plantations transported enormous hogsheads of tobacco, each weighing a full ton, to be assessed and stored at the massive Maryland State Tobacco warehouse complex before shipment to Europe or to be redistributed to the city’s many cigar factories.

Meanwhile, milled flour went southwards to South America in exchange for iron ore, sugar, guano, and coffee. And coffee! Baltimore imported more coffee than any other city in America! No wonder Baltimore should have doubled in population in twenty years!

Further bolstered by its growing position as the port and trading center for a South already fat and arrogant on cotton wealth, it should surprise no one that Baltimore should suffer minimally in the Panic of ’57 that had swept Philadelphia and the North. Such a city offered many prospects to a young attorney just starting out.

And Baltimore was closer to his fiancé in Frederick.

But in looking around the square, Jude began to have doubts. No one would assemble in such large numbers in Baltimore unless they were looking for trouble. Especially these days.

He grabbed Matthew. “Not everything is what it seems to be,” he warned. “These have not been peaceful times, not ever since Lincoln’s election. Let’s go to the courthouse now.”

“Don’t worry. I know what’s happening.” Matthew winked. “It’s the Palmettos.”

“Palmettos?”

Matthew nodded. “They are testing me to see if I’m worthy of joining their cause.”

“Palmettos?” Jude persisted, puzzled.

But Matthew didn’t explain. He pushed through the crowd and Jude followed, exerting effort to breathe through his muffler for the cold stung so hard.

“There’s almost as many people here as during the Democratic conventions last May and June,” Jude murmured. “I heard the drunken shooting till dawn. Even if the Democrats lost the election.”

“Only thirty-nine percent,” Matthew said, reminding Jude of Lincoln’s plurality victory in the four-way election featuring two Democratic candidates, Stephen Douglas of the North and John Breckenridge of the South, along with John Bell of the neutral Constitutional Union party.

“Lincoln should be ashamed to call himself President when two thirds of Americans didn’t vote for him!” the secessionist added. “And you know what happened on Election Day in Baltimore, and it’s all Mr. Lincoln’s fault!”

Jude did. Pro-Democratic gangs rampaged through the colored neighborhoods all day and even in his quiet part of town he’d come out of his polling station, after voting for the Constitutional Union party, to see a horde chase after a colored drayman.

When the elderly man fell, the youths poured blackened whitewash on his head and called him a Republican monkey. A nearby policeman watched the scene but only after the damage was done did he chasten the boys, and he also warned the colored man that Lincoln’s victory would be their race’s downfall.

“Lincoln can’t keep justice from the South,” boasted Matthew. “No one, least of all a tyrant from the Illinois prairies, can stop Baltimore from celebrating Georgia’s secession!”

A window flew open in one of the rowhouses and someone peered out to watch the growing crowd. Spectators appeared on the courthouse’s terrace. A group of men bumped into Matthew, who yelped.

Some of the newcomers went straight for the monument, joining others already waiting. There they stood, sallow-faced and hunched underneath their caps, the yobs and rowdies, hard-drinking men from the docks or railroad yards, or draymen who lugged goods around Baltimore.

Like the farmers in the country, these men had the weatherworn appearance of a life spent outdoors. Unlike the farmers, there was hardness in these expressions. A hardness from a lifetime of disappointment? A failed farmer became weary, a failed worker became angry?

“It doesn’t look like a rally in support of Georgia,” Jude warned Matthew, eyeing the bulging pockets of the patched coats. “A rally would be livelier,” he said, noting the unusual silence for the first time. Men should be shouting the latest secessionist news along with cheers or jeers from those who considered loutish behavior a right as sacred as the vote and hatred of the Negroes.

Straining to hear any conversation, Jude was startled when the waiting rowdies suddenly reconfigured. Someone must have given an order for the amorphous crowd split into two gangs on opposing sides of the squat Battle Monument.

The chatter on the sidewalks rose to a steady buzz. Two cabbies whipped their horses and drove their hacks away from the square. A closed carriage, a fancy black landau, waiting in front of the courthouse’s stone terrace wall, started to move before halting, the silver harnesses on the pale gray mares glinting in the sunlight.

A flock of pigeons flew from the Battle Monument and disappeared into the sky.

Jude’s heart started to race.

Something was going to happen.

He knew it as much as most people around him did. Every pair of eyes watched the rowdies in the square and was as studiously avoided in exchange.

Tension crackled; an atmosphere so real Jude felt it as much as the wind stinging his face.

“There’s going to be a fight,” he suddenly said. He didn’t know why, for although people expected Georgia’s secession, no one rioted when South Carolina seceded. Euphoria and drunken celebrations, yes, but not rioting.

Matthew grabbed his arm as one of the great windows of Barnum’s Hotel flew open.

****

To return to Table of Contents: Link

Stovepipe hat and jacket believed to have belonged to Abraham Lincoln. https://www.si.edu/object/abraham-lincolns-top-hat%3Anmah_1199660